Lucian Freud and Sue Tilley: The story of an unlikely muse

Tate photography, Joe Humphrys

Tate photography, Joe HumphrysLucian Freud’s paintings of benefits supervisor Sue Tilley set records at auction houses. She tells Cameron Laux what it was like to sit for one of Britain’s greatest artists.

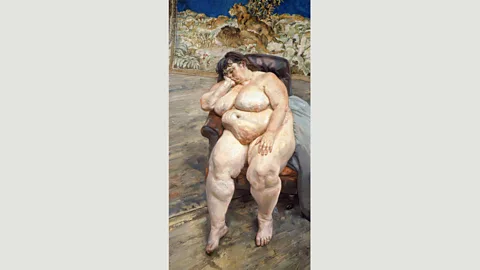

One of Lucian Freud’s more famous paintings depicts a fertility goddess having a nap on her sofa. She is naked and seems to be deep in unguarded sleep (her face is partly squished and she looks like she might be drooling). Despite this, she is majestic; she has curves on her curves, and they phosphoresce gently in shades of brown, pink, and white. How did the artist sneak up on her? Will he survive her wrath when she wakes up?

Lucian Freud Archive/Bridgeman Images

Lucian Freud Archive/Bridgeman ImagesNo need to worry. For one thing, the goddess isn’t actually asleep: Freud painted her in that pose in sessions spread over many months – he liked to paint from life, and he was fussy, layering and working oil paint until it looks like slathered mud. But for another, the goddess isn’t actually a goddess: she is Sue Tilley, at the time working as a supervisor in a government Jobcentre in London (the title of the painting is Benefits Supervisor Sleeping), and she is as generous on the inside as she is on the outside.

In person, Tilley has a lot of presence, and you realise that Freud’s paintings tap into this. She was in her 30s in the paintings; she is 60 now. She is very kind, dead honest, quick to smile. She has the startling sophistication of someone who has been around the block a few times. And what a block.

Sue Tilley

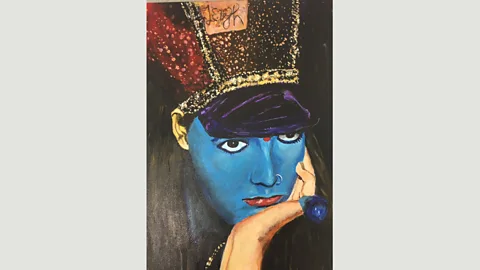

Sue TilleyTilley led a Technicolor life long before she met Freud: she was close friends with the ‘total’ artist Leigh Bowery and when she wasn’t at her desk in the office she was part of the anarchic clubbing set in London in the 1980s, centring on notorious nights with names like Blitz and Kinky Gerlinky, but especially Bowery’s own creation, Taboo. The latter was one of the wilder and glitzier moments in a decade of egregious moments (polysexual, polysocial, polyeverything), and one of those avant-garde detonations whose effects can still be felt far away in the mainstream.

Wild nights

There is a large literature on the visual genius of Bowery. His exquisitely executed alter egos were nightmarish (in the fecund sense), often powerfully sexualised, sometimes purely beautiful, always resonant. Bowery ignored the boundaries of taste. He was a prodigy in all senses, but perhaps particularly in the old sense of an omen, a shooting star streaking across the night sky. Like so many of the remarkable gay men of that period, he was erased by Aids.

Sue Tilley

Sue TilleyTilley’s Instagram offers a mood board that includes her 80s adventures: she says she didn’t consider it a good night unless she’d got drunk enough to fall over at some point. Although Tilley was Dorothy in this Land of Oz, her place in posterity really is guaranteed by a series of four nude portraits which Freud did of her in the late phase of his career. All are likely to remain of art-historical significance.

Alamy

AlamyOf those, Benefits Supervisor Sleeping (1995) is probably, and deservedly, the most famous. Evening in the Studio (1993), the first of the series, has her sprawled on the floor with a seated girl apparently disinterested and reading a book in the background. The composition is an odd combination of domestic scene and crime scene. (Tilley says she was relieved when Freud bought the sofa because it was painful to lie on the floor for hours.)

Benefits Supervisor Resting (1994) depicts Tilley in the corner of the sofa with her head lolling back, as if she’d just swallowed some poison; a position that could not have been comfortable either. Finally, in Sleeping by the Lion Carpet (1996) Tilley is shown sleeping upright in a chair, facing us. I like that painting because the juxtaposition with the lions in the background suggests that Tilley’s grandeur is epic. (Quite true, I’d say.) She hates that painting because she says it makes her look awful.

Freud once revealed: “If I am putting someone in a picture I like to feel that they’ve fallen asleep there or they’ve elbowed their own way in: that way they are there not to make the picture easy on the eye or more pleasant, but they are occupying the space of my picture and I am recording them.” This unflinching gaze produced works that resonate deeply with viewers. “The task of the artist,” Freud said, “is to make the human being uncomfortable, and yet we are drawn to a great work of art by involuntary chemistry, like a hound getting a scent; the dog isn’t free, it can’t do otherwise, it gets the scent and instinct does the rest.”

All of Freud’s paintings of Tilley are in ‘private collections’, ie the hands of extremely rich men, capable of paying tens of millions of pounds for the privilege of gazing on her ‘flesh’ (Freud’s word). For instance, Roman Abramovich set a then-record for the largest amount paid for a painting by a living artist when he bought Benefits Supervisor Sleeping in 2008 for £17 million ($33.6 million at the time). If you want to see it, you might want to become very good friends with him. Be prepared to become a Chelsea er, because he owns that football club too.

Lucian Freud Archive/Bridgeman Images

Lucian Freud Archive/Bridgeman ImagesAnother one, Sleeping by the Lion Carpet, is on display as part of the show All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a Century of Painting Life, currently on at Tate Britain in London until the end of August 2018. That painting is on loan from a billionaire who among other things owns Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. Catch it before he hangs it back up in his guest toilet.

Benefits Supervisor Resting, meanwhile, has been described as “Freud’s ultimate tour de force, a life-size masterwork in the grand historical tradition of the female nude, painted obsessively with intense scrutiny and abiding truth”; when it was sold at auction in 2015, Christie’s head of post-war art Brett Gorvy said that the painting “is recognised internationally as Freud’s masterpiece and proclaims him as one of the greatest painters of the human form in history alongside Rembrandt and Rubens”. Gorvy described the painting as “a triumph of the human spirit, showcasing Freud’s love of the human body”, commenting on Tilley that Freud “observed every inch of her with an uncritical eye almost daily for more than nine months”.

Alamy

AlamyAccording to Gorvy, Tilley “is calm and confident, relaxed and comfortable in her own skin. She is very much in control, taking on the artist and the viewer. A contemporary take on the Odalisque and the fertility goddess, with her head flung back, she exudes an intriguing ambiguity, implying ecstasy, defiance and the deep exhale of peacefulness.” Benefits Supervisor Resting went on to sell for £35 million ($56 million).

None of the money that has rained down on her representations has made its way to Tilley. When she was posing for Freud he paid her a small daily fee (she told The Guardian that she thought she’d been picked out by Freud as a life model because she represented good value for money – “He got a lot of flesh”).

Yet, she says, she had the pleasure of his company. She liked him because he was ‘hilarious’ and loved to gossip with her. (Tilley met Freud through Bowery, who was also being painted by him.) She found Freud’s mercurial personality fascinating: she says he could be “mean, extremely generous, grumpy, funny, loud, quiet”; also manipulative, but perhaps in a rather charmingly transparent way. Grumpy seems to have won out, because eventually he dropped her as a friend after taking offence at an offhand remark she made.

Tate photography, Joe Humphrys

Tate photography, Joe HumphrysFreud gave her some etchings, which she sold years ago because she was short of money, but otherwise she has no mementos. She says he didn’t phone to say thank you after his first painting of her sold for a large sum of money.

She has a £60 printed copy of Freud’s portrait of Leigh Bowery (now in Tate Britain) on the wall of her flat. In 1997 she published Leigh Bowery: The Life and Times of an Icon, which must be his most definitive biography. It also captures the London club subcultures of the Bowery era very vividly.

From muse to maker

Tilley has retired from the Jobcentre and moved from London to a quiet seaside town in East Sussex. But she is not dozing off. She enjoys frequent visits from artists, creatives, and journalists from around the world who want to talk about Freud, Bowery, and Tilley. And the walls of her flat are vibrant with art, some of it by friends, but most by her. She learned how to draw when she was young and then dropped it, but she has recently taken it up again. She is good.

Sue Tilley

Sue TilleyThrough friends and accident, she ended up having a large solo show of paintings and drawings at an east London gallery in 2015. It caught her a little by surprise, but got her working flat out to produce pieces to fill the gallery. Her style is sketchy, maybe a little cartoonish, self-assured. The effect of her anti-aesthetic is charming. She focuses on the personal: portraits of friends, drawings of everyday objects which she sometimes affectionately calls ‘boring’ but which she loves.

Tilley elaborates on this low-key universe in a further step in her artistic career: her collaboration with the S/S18 Fendi Men’s collection, where luxury clothes and bags are decorated with her pictures of desk lamps, bottle openers, banana skins, cups of coffee. Fendi calls this “corporate escapism” and it is undeniably fun; although you would need to be escaping after light-heartedly robbing a bank, since a T-shirt with a drawing of a martini goes for about £480. I suppose one can’t really complain, since a painting of Tilley goes for upwards of 35,000 times that amount. It is long past time that she got a bigger piece of the action.

Sue Tilley

Sue TilleySo, onward for Sue Tilley and her remarkable life. At one point she shows me a nude self-portrait that she painted on a plate for a charity auction. The image echoes Benefits Supervisor Resting, except she is sitting upright and alert, her eyes open. She tells me the title is The Benefit Supervisor Has Woken Up. I would say she never went to sleep. Such a pity that Freud isn’t alive to sit for her.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.